There is a Javanese phrase “Sangkan Paran Dumadi” , which means “the origin and destiny of being”. In Indonesia, it is common to be greeted not with ‘How are you’, but rather with the question “Kamu dari mana?”, which translates into “Where have you arrived from?”. This question, in the words of artist Alexander Sebastianus, “revisits the awareness of our locality, origins and becomings”. It invites one to consider how one is located, not just geographically, but also within a social and even cosmological matrix. As author Fred B. Eiseman Jr notes, in his study of Balinese culture and spirituality, “a direction describes a vector not just in physical space but in cultural, religious and social ‘space’ as well.”¹ Art historian Patrick Flores concurs, proposing that “(i)n this universe of language, origin is more than just locus or inscription that hews, oftentimes even overdetermines, identity. It is a cosmological condition.”²

Dari, Inquiry of From

Sebastianus’s solo exhibition, titled Dari, is a deeply personal anthology exploring these myriad points of origin, or ‘from’s. His work on ‘dari/froms’ is part of a continuous ethnography, cartography, and inquiry into modes of existence. In his search for points of origin, Sebastianus references philosophers Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of the rhizome, a non-hierarchical sprawl of various roots, shoots, and possible trajectories, always open to interconnection and entanglement with others. Rooted in his lived experiences of being raised in a multi-religious household, and coming of age in a society and culture in transition, Sebastianus locates his ‘being’ on this constantly shifting plane, freeing himself from constricting binaries or definitions shaped by institutions such as family, religion, and society; or terms such as artist /craftsman /ethnographer /shaman. Aligning himself with the experimental praxis of artists who embrace flux, such as Joseph Beuys and Marina Abramović, Sebastianus inhabits multiple roles and positions all at once, in order to forge new directions and possibilities of being. Drawing freely from the various cultures and knowledge-systems he has lived between and experienced, from his academic education in the West to the mastery of making as ritual gleaned from the weavers in his grandmother’s hometown in East Java, Sebastianus interweaves myriad threads of ‘knowing’ or 'understanding’, to propose his own tapestry of being, becoming and belonging. In approaching Sebastianus’s work, it is important to understand the distinction the artist makes between different terms employed to refer to ‘art’ in Indonesia. The first, and most commonly encountered, is seni, a direct translation of ‘art’ or the German ‘kunst’

THE MATERIALITY OF BELONGING

The other is Sani, a word derived from Sanskrit, meaning worship, service, or ways of living.³ Seni is a relatively modern word; prior to this, there was no word for ‘art’ in Javanese. This understanding and practice of ‘art’ as we know it today, is, in the artist’s words, “rooted deeply in Eurocentric canons and modernization, to the point where to make art is to be heavily attached to the white wall, the market and academia”⁴. Sani on the other hand, can be understood as an offering, a search for oneself through the search of an unknown. With sani, the end product is not a commodity, nor is it always intended for public display. Instead, it is often more of a private ritual: internalized, or one shared within a close community of family and friends. What is often left are remnants or traces, rather than ‘whole’ artworks. While working on his ethnographic thesis on decolonizing or reclaiming indigenous values of ‘art’ through the contemporary, Sebastianus decided to continue this inquiry of Sani, not only as a researcher but as a practitioner. These principles, from the practice of Sani, guide his making – ‘art’ as a way of living, art as being.

Dari restitutes elemental materials of symbolic significance to Sebastianus’s work: rock, water, and cloth. The materiality of these objects has long been associated with rites and rituals, and Sebastianus draws on this symbolic lineage while contextualizing these objects with his own lived experiences. In bringing new ontology to the materials, Sebastianus re-sacralizes and transforms the objectivity of every particle into a processual ensemble that co-exists with his being. In weaving this object ontology, Sebastianus plays the role of a magician or shaman, re-enacting his own performative rites (Kembali Dari), and creating relics and sacred shrines (Tirta Dari) of his own. Sebastianus also revisits his own collection of artifacts, ranging from childhood teeth to heirloom batik cloth, images and files stored on his mobile phone, his grandmother's wig, and so on. This visitation, re-assembled, allows Sebastianus to articulate his narrative of origins, and further understand our association with belonging(s). In this way, Sebastianus weaves between his training as an ethnographer in his study and collection of artifacts, and his role as a magician or artist in creating new practices and personal rituals from these objects, transforming their import and agency by way of context and their relationship with other objects. Collectively, these assemblages inspire as well as articulate narratives of origins, being, and becoming.

A Particle, A BODY

"

A body is a particle, consisting particles of froms.

I was born from a from, to die and

become particles of the possible froms.

A rock is a particle that came from, from.

A rock consisting millions of froms, millions of dust,

of particles that geologically creates and

forms an entity or a being.

The rock is a body that resembles my from, a from.

”

—Lisan #27, A. Sebastianus

Dari opens with a rock, a poetic metaphor for the coalescing of a million particles or points of origin (‘from’s), compressed through time in a single, solid object. This unassuming object is what links us to the stars and galaxies; in its enduring mass it spans eons, bridging the present with the past. It is the stuff of the universe, a perfect encapsulation of the macro-cosmos in the micro, the one-in-many and the many-in-one. Shaped into monuments, temples and steles, it carries humanity’s attempts to inscribe the divine, to worship and commemorate.

The body or ‘being’ are also composed from particles – a million measures of time, images, shapes and colours of memory held in our soul, the possessions and heirlooms that define us and our origins, passed from one generation to the next. Sebastianus honours this lineage in works that combine two generational methods of image-making: photographic print and batik, the Javanese wax-resist dye technique. These works, which the artist describes as ‘studies’ , investigate the shape of ‘being’, its many layers, and its constitution. Pixelated image-particles, representative of memories and belongings, are imprinted on cloth and waxed over, before the cloth is then dipped into dye. This batik process is an apt metaphor for unveiling, as the wax holds the initial image imprinted onto the fabric, resisting the dye that otherwise shrouds the rest of the textile in darkness.hese ‘studies’ are also translated into three-dimensional forms, where Sebastianus uses actual particles gathered from the belongings of his loved ones – the charred remains of their clothing, shards of glass, sand from their home – shaping these into rock-like sculptures. Arranged within the exhibition space, they recall the stones that silently mark the boundaries of sacred sites. Here, they embody Sebastianus’s practice of Sani: making as offering, and a search for being.

These rocks embody; they also evoke a body. Visual as well as metaphysical parallels are drawn between the rock and that of Sebastianus’s prostrate form. His fetal position signifies a return to an origin or ‘from’. At the same time, it also suggests the gesture of humbling or offering the self. It is also a grounding – the body pressed against the earth, receiving its energy and removing any distinction between the human and the terrestial.

KEMBALI DARI - RIVERS OF FROM

These ideas are developed in two works: Sangkan Paran (Mother Tongue) and Kembali (Return). The latter documents the artist’s private ritual that he performs at bodies of water in order to ‘let go’ and at the same time, return or remember. Sebastianus has enacted this ritual at sites of significance to him, including the sacred Ayung river in Bali where he has his studio, Parangtritis shore in Yogyakarta – another body of water considered to be of great spiritual importance – as well as at his grandmother’s grave in South Jakarta. In the contemporary art world, this may be construed as a performance, but for Sebastianus it is a wholly personal rite, free from any religion but no doubt informed by a constellation of origins, from the practice of yoga to spiritual prostration, and even the work and ideas of artists such as Marina Abramović who speaks of the body as a ‘portal’ between realms, and for whom the often punishing conditions she endures during a performance are akin to the repetitive prostrations enacted by Buddhists: a kind of spiritual or bodily labor with no obvious use or ends, but made instead as an offering⁵.

In Kembali, Sebastianus’s body, curled up in balasana (child’s pose), is juxtaposed with images of bodies of water, documenting the artist’s personal rite but also evoking a return to the waters of the womb, an idea extended in another work in the exhibition titled Sangkan Paran. Here, the symbolism of water is explored, first as a synonym for the womb and origins, and secondly, as in the installation Rahim Tirta, in a more spiritual context, where it is held in a cross-shaped basin that at once recalls the crosses in church, the shape of the table in Sebastianus’s family home, as well as that of his grandmother’s Buddhist mandalas. The artist reflects that since young, he had attached a great import to water, relishing the sensation of the liquid on his skin and the feeling of cleansing and invigoration that it imparted. It was only later in adulthood that he learned of its importance in different spiritual rites and cultures: the Islamic practice of wudhu or self-cleansing before prayer; water baptism in the church to symbolize rebirth; the Buddhist tenet of impermanence and the unceasing flow of life, for which water is an apt metaphor; and the celebration of agama tirta, or the religion of water, in Balinese spirituality. In the words of the artist, “The water contains no color, yet reflects colors of from”, a testament to his syncretic and blended upbringing, and how the language of contemporary art, with its minimalist yet highly evocative form, is an apt vessel for distilling and holding a myriad ‘from‘s.

Poised above this personal, sacred well is Akar Temurun, an installation that evokes bloodlines as well as rivers returning to a larger body of water. Composed from a personal collection of archival photographs, this work is Sebastianus’s attempt to re-root himself, to uncover points of origin, while at the same time putting out new shoots to extend his journey of self-discovery. Like many of his generation who grew up in Indonesia during the Reformasi years, Sebastianus often felt adrift and rootless in his blended ethnic and cultural identity. He was raised as a Catholic in a predominantly Muslim society that was rapidly making itself over with professions of a new democracy and development. The gloss of modernity – in the form of malls and international franchises – papered over a collective amnesia, with large chapters of history whitewashed from textbooks. In Sebastianus’s own words, “There were no roots but branches, branches towards the modern/future. ” A common thread that runs through much of contemporary art in post-Suharto Indonesia is that of a search for identity and origins, of recuperating forgotten histories or repressed social upheavals and traumas. Sebastianus’s mapping of bloodlines, parentage, and belong-ings in Akar Temurun is informed by this lacuna, an ongoing personal project to understand the enmeshing of relations and the many

‘froms’ that lead to the ‘arrival’, here and now. This thread of searching is continued in expanded form, in the work An Anthology of Froms. Like an assiduous ethnographer, Sebastianus has assembled a collection of images, a kind of private archives or archaeology, that represent a multitude of ‘froms’.

The artist likens these to pusaka, traditional heirlooms passed down from one generation to the next, and often rarely seen or handled unless during an occasion of great significance (such as birth, marriage, death). Here we find the threads that have constituted the artist’s journey of being and becoming to date. Within this anthology, the motif of the stone recurs, this time appearing as a black mass against a background of pixelated images. Its presence returns us to the form and image that opens the exhibition, reminding us of beginnings or origins even as it closes a narrative cycle, and completes a (re)turn.

Is this shape a solid, impregnable mass – the weight of certainty of something enduring – or is it a void? Is it the lacuna around which Sebastianus’s journey of enquiry circles?

¹ Fred B. Eiseman, Jr., Bali: Sekala and Niskala. Essays on Religion, Ritual, and Art, 1990. Tuttle: Tokyo, Vermont, Singapore. pp. 3.

² Patrick D. Flores, “Address of Art: Vicinity of Region, Horizon of History ” , in Charting Thoughts: Essays on Art in Southeast Asia, 2017. National Gallery Singapore, pp. 12.

³ Deni Junaedi, Estetika: Jalinan Subjek, Objek, dan Nilai, 2016, 2017, 2021. ArtCiv: Yogyakarta, pp. 177.

⁴ Ho See Wah, “Fresh Faces: Alexander Sebastianus Hartono”, Art & Market, 25 November 2020. https://artandmarket.net/dialogues/2020/11/25/fresh-faces-alexander-sebastianus-hartanto

⁵ Clare Harris, “Portals and Gates: Conversation with Marina Abramović” , Pitt Rivers Museum, pp.50. https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/files/Marina_Abramovic_interview_Clare_Harris.pdf

-

-

-

Alexander Sebastianus, Tubuh #02, 2023

Alexander Sebastianus, Tubuh #02, 2023 -

Alexander Sebastianus, Tubuh Di'antara #03, 2023

Alexander Sebastianus, Tubuh Di'antara #03, 2023 -

Alexander Sebastianus, Batubuh #01, Batubuh #03 and Batubuh #07, 1995-2023

Alexander Sebastianus, Batubuh #01, Batubuh #03 and Batubuh #07, 1995-2023 -

Alexander Sebastianus, Bayangan Dari #01 (Remnants of From), 2024

Alexander Sebastianus, Bayangan Dari #01 (Remnants of From), 2024

-

Alexander Sebastianus, Anthology of Froms, 1995 - 2023

Alexander Sebastianus, Anthology of Froms, 1995 - 2023 -

Alexander Sebastianus, Bayangan Dari #02 (Remnants of From), 2024

Alexander Sebastianus, Bayangan Dari #02 (Remnants of From), 2024 -

Alexander Sebastianus, Semua dan Segalanya #03, 2024

Alexander Sebastianus, Semua dan Segalanya #03, 2024 -

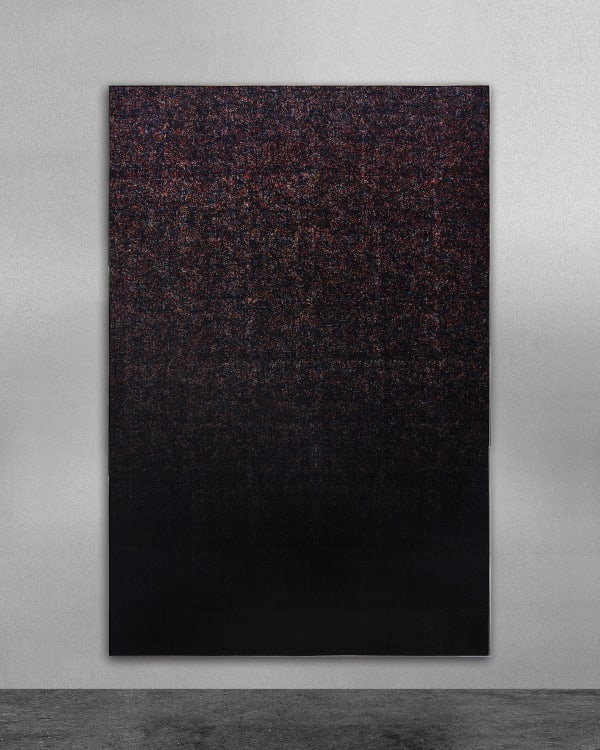

Alexander Sebastianus, Particles of From #01 - Ascending, 2024

Alexander Sebastianus, Particles of From #01 - Ascending, 2024

-

Alexander Sebastianus, Barong - Lot #24-01, 2023

Alexander Sebastianus, Barong - Lot #24-01, 2023 -

Alexander Sebastianus, Tubuh #01 , 2023

Alexander Sebastianus, Tubuh #01 , 2023 -

Alexander Sebastianus, Particles of From #13, 2024

Alexander Sebastianus, Particles of From #13, 2024 -

Alexander Sebastianus, Barong - Lot #25-02, 2023

Alexander Sebastianus, Barong - Lot #25-02, 2023

-

Alexander Sebastianus, Semua dan Segalanya #02, 2024

Alexander Sebastianus, Semua dan Segalanya #02, 2024 -

Alexander Sebastianus, Rahim Tirta, 1995 till end

Alexander Sebastianus, Rahim Tirta, 1995 till end -

Alexander Sebastianus, Relics of a Migrant - Lot #2 , Beggining till end

Alexander Sebastianus, Relics of a Migrant - Lot #2 , Beggining till end -

Alexander Sebastianus, Titik Dari #6, 2024

Alexander Sebastianus, Titik Dari #6, 2024

-

Alexander Sebastianus, Titik Dari #04, 2023

Alexander Sebastianus, Titik Dari #04, 2023 -

Alexander Sebastianus, Titik Dari #5, 2024

Alexander Sebastianus, Titik Dari #5, 2024 -

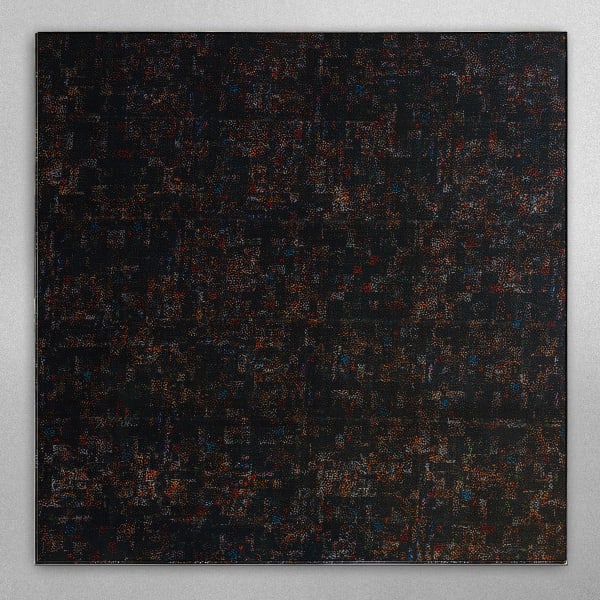

Alexander Sebastianus, Particles of From #14, 2024

Alexander Sebastianus, Particles of From #14, 2024 -

Alexander Sebastianus, Particles of From #04, #05 and #06, 2023

Alexander Sebastianus, Particles of From #04, #05 and #06, 2023

-